Ophelia: A Florilegium

- Annika Nori Ahlgrim

- Jan 18

- 2 min read

Ophelia Does Not Ramble

Ophelia’s flower speech in Hamlet is often taught as the moment she “goes mad.”

Her language becomes fragmented.Her behavior becomes difficult to interpret.She stops speaking in the forms that the court recognizes as rational.

But this reading assumes that coherence is neutral—and that breakdown is the only explanation for altered speech.

This project begins from a different premise.

What if Ophelia does not lose language at all?What if she changes it?

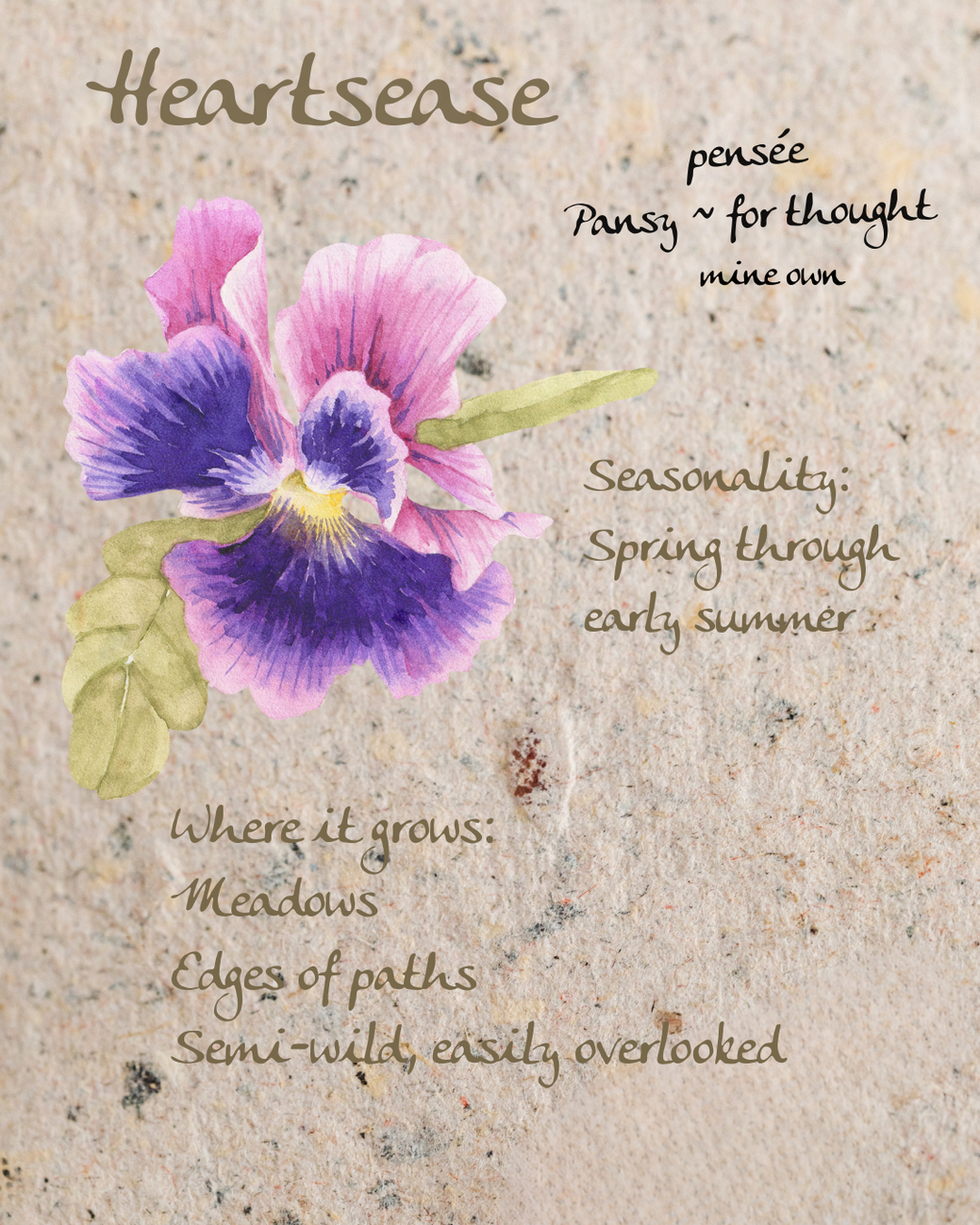

Flowers Chosen as Speech

In early modern England, flowers were not decorative abstractions. They were moral, medicinal, and social signifiers—used to communicate memory, repentance, loyalty, accusation, and grief.

Ophelia’s flower speech occurs only after:

her father has been killed,

her romantic relationship has been weaponized against her,

and every sanctioned avenue of speech has become unsafe.

When direct accusation would be dangerous, she turns to a language that cannot be punished.

Not because it is meaningless,but because it is deniable.

The flowers Ophelia distributes are addressed.They are directed.They are socially legible to the people receiving them.

This is not rambling. It is testimony delivered under constraint.

The Florilegium

This florilegium imagines Ophelia as someone who already knows the language she will later speak.

Before the court scene, she is attentive, observant, and educated in domestic botany—the kind of knowledge traditionally held by women and passed quietly through care rather than institutions.

The book exists before the crisis.

What changes is not her understanding, but her need.

In returning to these entries, she revises them:

meanings sharpen,

margins darken,

some symbols are activated,

others are withheld.

Most notably, the violets—associated with faithfulness—are rendered no longer viable.“They withered all when my father died.”

This is not an emotional flourish. It is an ethical recognition.

Grace is Not Silence

One of the final marginal notes reads simply:

grace ~ not silence

This is not an accusation aimed outward. It is a private permission.

In early modern usage, grace is not comfort. It is moral allowance—the space in which one acts despite fear, despite judgment, despite appearing improper.

If Ophelia asks for grace here, it is not to be forgiven. It is to speak.

Why This Matters

Ophelia’s “madness” has often been used to teach fragility.

But what if it teaches something else?

What if it shows us how women adapt language when power refuses to hear them?How knowledge learned for care becomes rhetoric under pressure?How survival requires choosing not just what to say, but how to be understood?

This florilegium does not attempt to redeem Ophelia by making her legible on patriarchal terms.

It listens to her on her own.

Continuing the Conversation

This piece is part of Women & Anger in Shakespeare, a live, small-group workshop series that reads Shakespeare’s women as rhetoricians, not symptoms.

Week One begins with Ophelia.

We read her closely. We read her together. And we ask what her strategies might still teach us.

Ophelia — Week One

January 21, 2026 | 6:30pm-8:30pm

.png)

Comments